Looking up at the stars after an abhorrent and senseless tragedy, the title character in Nikos Kazantzakis’ Zorba the Greek, turns to the narrator, a man who had lived entangled in books, and pleads:

‘What can be happening up there?’ . . . ‘Can you tell me, boss/ he said, and his voice sounded deep and earnest in the warm night, ‘what all these things mean? Who made them all? And why? And, above all’ – here Zorba’s voice trembled with anger and fear – ‘why do people die?’

‘I don’t know, Zorba,’ I replied, ashamed, as if I had been asked the simplest thing, the most essential thing, and was unable to explain it.

‘You don’t know!’ said Zorba in round-eyed astonishment . . . ‘Well, all those damned books you read – what good are they? Why do you read them? If they don’t tell you that, what do they tell you?’

‘They tell me about the perplexity of mankind, who can give no answer to the question you’ve just put me, Zorba.’

‘Oh, damn their perplexity!’ he cried, tapping his foot on the ground in exasperation. (Kazantzakis, p.288)

Why art? Why literature? What good is it? What is its purpose? In the words of William James, what is the “cash value” of a song? Or echoing Milosz, “What is poetry, which does not save nations or people?”

This essay presents some preliminary thoughts on how True Art – whether it is poetry, literature, painting, sculpture, dance, music, etc. – improves our lives, and connects us to the best aspects of ourselves.

What is the Purpose of Art?

Art can do many things. Not every work performs the same function, and not all consumers have the same needs from art. As such, different works may do very different things. The quality of a work and whether it achieves its aim can be assessed, but the goal of Harry Potter or Steven King for example, is different than that of Dostoevsky or Garcia Marquez. (For more on how to assess art, see the essay here)

Several of these functions are set forth below. As you consider them, think about your favorite works, and what needs they fulfill.

Basic Functions of Art

1. Offer an Escape. Sometimes all we want and need and long for is to just get away. An attorney may spend her time helping victims of crime. Intellectually fulfilling and spiritually rewarding. Heavy and exhausting. At the end of a long day she may not want to grapple with a text or confront existential issues. Sometimes we just want to relax, laugh and escape.

2. Provide Positive Emotions. Some works are pleasant and beautiful and evoke positive emotions. This can make our time here on earth more special and enjoyable, but these emotions are also a resilience strategy. Art can serve as a reminder of what is good in the world. It can inspire in us the humility, compassion, and awe that make us more human, or the courage we need to keep our heads high when things are hard or overwhelming. The arts can point us to the miraculous, when we are caught, as Rothko put it, between “the bomb and supermarket”. So often it seems, the world are living in, is in need of miracles.

3. Provide a Safe Space. Art can provide a place of safety, order or a sense of home. This can be the physical space itself. In New York after September 11, museums opened and restored a sense of normalcy. As our friends and neighbors emerge from the long, soft panic of isolation from the pandemic of 2020, museums can again offer a feeling of shelter.

The safety provided by art can also come from the work itself, such as the geometric order of a piece of art, or the structure of poem. Personally, there is a music and resonance in works of Walcott, Milosz and Whitman, that instantly returns me to a sense of home.

4. Instill Hope. Similar to “positive emotions” above, by pointing to what is right with the world, the arts can remind us of the good that exists around us every day. They can provide hope when things are difficult, and gratitude when life seem bleak. In this way, art can serve as a counterbalance to our “negativity bias,” that propensity to notice and attend to the things that are wrong and dangerous. Poet Adam Zagajewski reminds us that even with the inevitable injustice and loss, there is no contradiction in having Praise for the Mutilated World.[

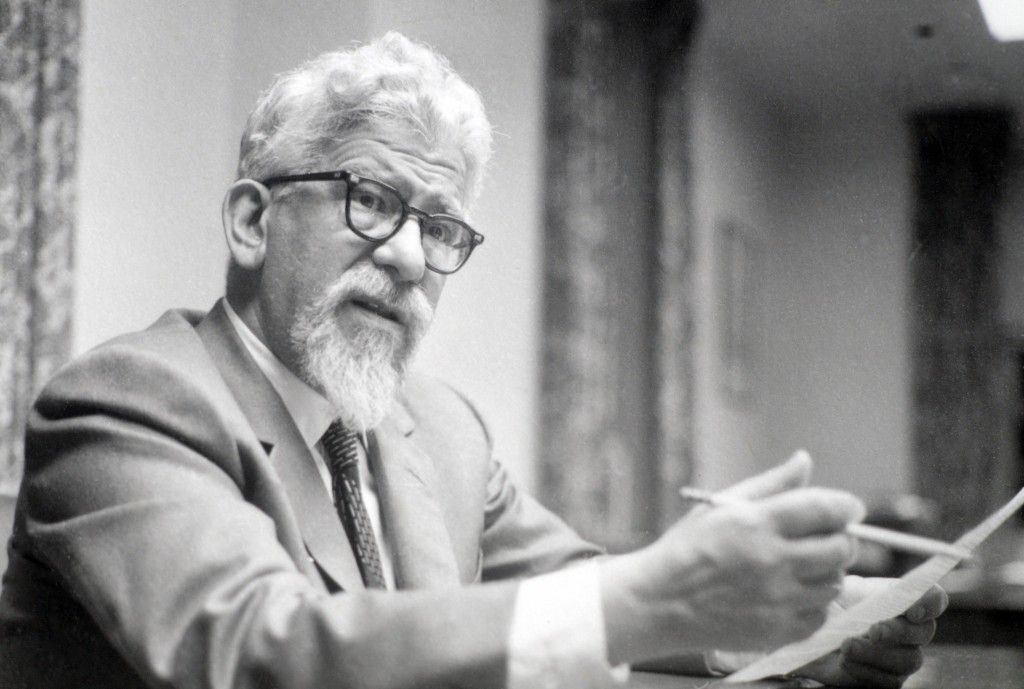

5. Reminds Us We Are Not Alone. Of course, not all art is beautiful or orderly or brings out good feelings and hope. Sometimes the heavy brush strokes or dark prose illuminate the worse impulses of humankind or the tragedies and inequities of life. What value does this provide? Commenting on the existential themes of his writing, Saul Bellow once said that people would say to him “We have to live this. Why do we have to read it too?”

Sometimes an artistic argument from the shadows can remind us that we are not alone. Hardship and suffering, loss and injustice are a part of every life. When we are in the midst of it, just trying to manage, and feeling like we can no longer hang on, art can help ease the burden by reminding us that we are not alone.

6. Enhance Mindful Connectedness to the World. More than once, I’ve heard a parent lament that their child was studying poetry or philosophy in college. Poets and artists are often caricatured as disconnected, or dreamers. Some are. However, there are disconnected lawyers, plumbers and businesspeople too. Rather than being something tangential to our lives, art can teach us to pay attention. With so many obligations and practical distractions, it is easy to miss the essential things right before our eyes.

When the artist chooses his or her images, they are pointing to what the character deems significant. A chipped teacup may have been mass produced, underused and insignificant in the arc of history. But to the character in Tarkovsky’s Mirror, it overflows with memory and meaning. By drawing our attention to the significance of everyday, simple things, art teaches us to pay attention to what can nurture us, make us more human, and connect us to one another. For poet Derek Walcott, “The teaching of poetry . . . is the greatest thing that can happen to any republic, because if you learn the craft of verse, then you can’t be fooled easily. You don’t take in rhetoric . . . [young poets] have to be devastatingly honest with themselves. If they can offer that to society, it is an immense good.[

7. Affirm or Change How We See the World. Not only does art make us more aware of our world, it can also effect the way in which we see the world. Art can support the firmly held beliefs we already hold. If your narrative is that life is tragic, you will find art, poetry, film, and scripture that confirm that belief. If for you, life is good and provides a reason for hope, you will find powerful, relevant art that will confirm those beliefs. When art affirms what we already believe, it can be an important source of stability and safety in our lives (see safety above).

However, the arts can also alert us to facts about the world outside of our usual narratives, challenging our foundations, and creating the possibility for growth: Political crises and injustices; or the fact that beautiful and hopeful things persist, despite the hardships and tragedies.

Transcendent Functions of Art

The functions of art listed above, are all reasonable and sufficient to meet legitimate needs of people trying to make their way in the world. However sometimes art does something more. There are certain artists, or works, that have the power to move the consumer to a condition of ékstasis where the individual is not just moved by the work, or in awe of it. Rather, they feel the work resonates at the same frequency as their soul and moves them beyond themselves. Joseph Campbell said this about James Joyce. Derrida said this of ideas from Levinas and Dostoevsky. Józef Czapski was kept alive in a Soviet prison camp by his memories of Proust. John Coltrane was canonized. In this sense, art, True Art, can also serve a transcendent purpose, and address more essential needs. For as Williams Carlos Williams wrote: It is difficult/to get the news from poems/yet men die miserably every day/for lack/of what is found there.

- Enhances Communion.

Art has the power to bring people together. Friends and family can connect around a work. They might go to museums and films together, or discuss literature and poetry, creating memories and sharing hopes and dreams.

Art can put us in intimate communion with an artist who has long since died. Doestoyeski’s struggle to reconcile the existence of God with the suffering of children feels relevant, raw and real. Rothko said of his own work You’ve got sadness in you, I’ve got sadness in me – and my works of art are places where the two sadnesses can meet, and therefore both of us need to feel less sad.”

Art can also connect us to the hundreds of millions of nameless people, lost to history, who struggled with the same raw adaptive imperatives which we face today. (See, we are not alone, above) We don’t read Herodotus for his historical accounts. They are as much a dream-poems as it they are history. We read him for the enduring human tale he offers of people trying to navigate all the horrors and wonders of a human life. Our lives are part of a much bigger, much richer narrative.

2. Art Opens Us, Makes Us More Human and More Complete

In its best moments, art can evoke something raw and honest in the consumer, a response that is wholly independent from the beliefs and feelings or the artist. We do not even have to understand the work for it to unexpectedly touch something we did not even know was there. The connection the art allows is intimate and personal, and starts a silent dialogue between us and our own lives, and while moving us beyond ourselves.

The sheets of sound and melodic patterns in Coltrane, or the abstract regions of color in Rothko, contain no political argument or story. There is nothing there that makes sense in any linear way. But as Rothko explained, he wanted art to take people somewhere where they could recover their humanity. This is why Coltrane was canonized and people will weep silently in front of one of Rothko’s paintings.

3. Art as Spiritual Act

In Celtic mythology there is a notion of “thin places”: spots where the distance between earth and heaven is a little bit closer. One need not believe in heaven or God to have an experience of the sacred, and to recognize the relevance of its poetic currency as we go about our daily lives. Art can act as a “thin place” too, bringing us closer to something divine or holy, and connecting us to the spiritual aspect of being alive.

It is not about any sort of “meaning” that we can verbalize. Zorba was looking for an answer that was neat and clean and made incomprehensible things reasonable and just. But there is so much about life that cannot be spelled out as if it were in the liner notes of an instruction manual. The fact that we struggle and work and everything can be undone in an instant by some accident of the universe. The fact that children suffer. The fact other human beings who also suffer and grieve and love, will take advantage of the vulnerable. People get COVID or cancer or die alone or of a broken heart. We can rationalize and justify and find reasons for hardships that help us understand how individual pieces work in isolation. But narrow answers will never satisfy broad questions. And the need for reasons that make linear, literal sense of things, assume only one desperate dimension of our lives.

Art allows us to stand in the discomfort of not having these sorts of reasons, and connects us, through emotion and intuition, with three crucial parts of being human. It gets is spiritual power, its highest relevance, when it brings all of the essential aspects of our lives into authentic alignment; when it bring us into (i) communion with one another, (ii) clarifies and connects us with our own humanity and (iii) helps us transcend the narrow spaces in which we draw our numbered breaths.

Andrei Tarkovsky called film an act of prayer. What is prayer? For Elie Wiesel, prayer is any combination of words that brings people closer together.] Helping us to letting go of ourselves, and to connect to one another through compassion, forgiveness, hope, love, joy, trust, awe, and gratitude – the spiritual emotions – that is what art does for us, in its highest moments.

And with everything art offers, the safety, beauty, companionship, hope, alignment and grace – the relationship is reciprocal. In the words of Rabbi Heschel, we should live our life as if it were a piece of art.

I would say to young people

a number of things, and I have only one minute.

I would say — let them remember

that there is a meaning beyond absurdity.

Let them be sure that every little deed counts,

that every word has power,

and that we do — everyone — our share

to redeem the world, in spite of all absurdities,

and all the frustrations, and all the disappointment

And above all, remember that the meaning of life

is to live life as if it were a work of art.

(Abraham Joshua Heschel)

©2020,

John Albert Doyle Jr.

[i] See Adam Zagajewski, “Try to Praise the Mutilated World” from Without End: New and Selected Poems. (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002) https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/57095/try-to-praise-the-mutilated-world-56d23a3f28187

[ii] Walcott, interviewed by Glyn Maxwell, Lannan Podcasts November 20, 2002 . 49:20 https://podcast.lannan.org/2009/07/16/derek-walcott-with-glyn-maxwell/

[iii] William Carlos Williams, Asphodel, That Greeny Flower

[iv] “What is prayer? You take words, everyday words, and all of a sudden they become holy. Why? Because there is something that separates one word from another and then you try to fill the vacuum. With what? With whom? With what memory? With what aspiration? So when words bring you closer to the prisoner in his cell, to the patient who is dying on his bed alone, to the starving child, then it’s a prayer.” – Elie Wiesel, One Generation After.

Pingback: Literary Sommelier: How Do We Assess Literature – Sean Doyle