How do we judge a work of art? Can we meaningfully compare Tolstoy and Dickens, or Austin and Proust? Is it a purely subjective matter? Or are some works objectively better than others? When someone recommends a book to us, how are we to tell if it is one that we will enjoy?

Just as there are sommeliers of wine and whisky, when assessing a work of art, we can acknowledge the role of personal tastes, and yet still give an objective assessment of the quality of a work. Whether assessing a painting or a poem, a piece of music or film:

- consider the purpose of an individual piece of art. Not all works perform the same functions or roles, and not all consumers have the same needs or wants from art. The goal of Harry Potter or Steven King is different than that of Dostoevsky or Garcia Marquez. I propose various functions of art, here.

- Next, when considering a particular work, there are objective attributes that can be measured (e.g., Does it require skill, is it beautiful, does it speak to the human condition, does it advance the craft, etc.).

- The importance of each such attribute, however, is a matter of subjective value (e.g., someone judging Duchamp’s “Fountain” favorably would likely not place a high need on “skill” or “beauty”).

- Likewise, the individual, objective attributes can be effectively expressed in very different ways. The reader’s preference, will also be a matter of subjective value. Thomas Wolfe and Hemingway both write beautifully, but although a reader who values Hemingway’s sparse style may be able to appreciate Wolfe, she may be intolerant of him.

Considering different theories in aesthetics, this essay attempts to plot the objective attributes one can consider when assessing a work of literature.

What is important for you in a piece of literature? Does the story matter? If so, classic works lacking narrative structure will be maddening and incomprehensible. If a poetic flourish is an essential quality, then other masterpieces will feel as dry as a legal brief. To assess the quality of work, and one’s preferences, consider some combination of the following factors:

Technical Ability

There are several ways technical ability can be expressed: The Story; How Language is Used; and Technical Style.

Technical Ability (story)

Some people are drawn to a book because the story itself is well told and engaging. Huckleberry Finn is fun to read. Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose addresses semiotics, biblical analysis, and medieval studies, but is also a page turning historical murder mystery.

Contrast this with Jack Kerouac’s On the Road or Italo Calvino’s If on a winter’s night a traveler. A lot happens in Kerouac’s novel, and there are many colorful characters. But there really is no “story” in the traditional sense. Calvino’s novel tells about you (i.e., the reader) trying to read his novel, only to discover that the copy of your book only contains the first chapter. As you search for the missing chapters, you end up reading wholly unrelated chapters from completely different books. Extremely innovative and mind-bending, but it can be frustrating if you are looking to be gripped by a traditional linier tale. In conducting the assessment, these novels might fall short on the virtue of “Story”, even though they are remarkable and excel in other virtues.

Technical Ability (Style of Prose)

Authors can use language in different ways to express their art. Armed with a poetic flourish, some paint the page with elaborate and ornate prose. Thomas Wolfe has a “big” poetic style of prose that can sweep the reader away. Hemingway, on the other hand, is famous for his tight, efficient in use of language. To highlight the contrasting style, he even referred to Wolfe as “the over-bloated Li’l Abner of literature”. Each approach requires a great deal of skill, and different readers will place different values on the two approaches.

Technical Ability (Use of Language)

Aside from the author’s style of prose, the he or she can provide tremendous merit in how they use the language. These include the author’s use of symbolism, such as in Melville’s Moby Dick, or the complex overlapping layers of the story, such as in Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s 100 Years of Solitude. The author might introduce innovations that advance the entire cause of literature, as did Cervantes in Don Quixote or Joyce in Ulysses.

Psychological Depth

A psychological honesty and depth can make the characters real, credible and relatable. This too can be expressed effectively in different ways. Dostoyevsky was brilliant at igniting the existential forge at the center of a character’s subconscious. Tolstoy was much more subtle, but the reader of War and Peace, understands the “why” behind every raise of an eyebrow, of every action and every failure to act.

Richness of Ideas (Philosophic depth)

Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, Mann’s Magic Mountain, Goethe’s Faust: Some novels are novels about ideas, almost philosophic texts disguised as narrative fiction. Ideas can often be communicated effectively, even when you cannot capture the subtly or beauty of the prose in translation.

Moral Stance

Literature can also assume a moral stance. Plato famously banned the poets who misrepresented the truth and emphasized the negative qualities of the gods. Is the work good for society, hopeful, or inspiring? Does it convey an important moral lesson or help us live our lives better? In the preface to Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, the author asserts “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written or badly written.” Nabokov’s Lolita is a famous example of this tension: Masterfully written, but a morally reprehensible topic.

Other Factors

There are other factors to consider from the field of aesthetics when assessing the quality of a work. If a work is to be relevant to our lives, does it reveal some insight into reality?

Or, some theorists argue one should consider whether the work conveys the artist’s feelings. I list this below, but am biased against it. Whether the author expresses his or her feelings is only of value to the reader if that honesty of expression opens something personal in the reader. That is the valuable part. Not whether the author gave expression to what they were feeling.

Another factor that should be considered is whether the work is enjoyable. This by itself does not make a work “great”. However a work that advances the field, is psychologically honest and philosophically rich, is so much better if it is also a joy to read.

Final Test

I also considered various one question “tests” with which we could measure the greatness of a work. A popular one is asking what one book you would take with you if you were to be stranded on a desert island. This question poses practical problems. Aside from wanting to choose a book on “boat building” or “survival in the tropics”, the possibly of long term isolation would skew the choice away from certain picks. Novels involving psychologically complex human relationships, would be less attractive when stranded all alone. (I am reminded of the polar explorers who were almost driven to murder, from reading Dostoyevsky while lockdown during the long winter at the South Pole.)

There are however certain books that I return to, or that come back to me, over and over. They raise issues and renew their relevance, as I go about my life. This in itself is a measure of a certain greatness and relevance.

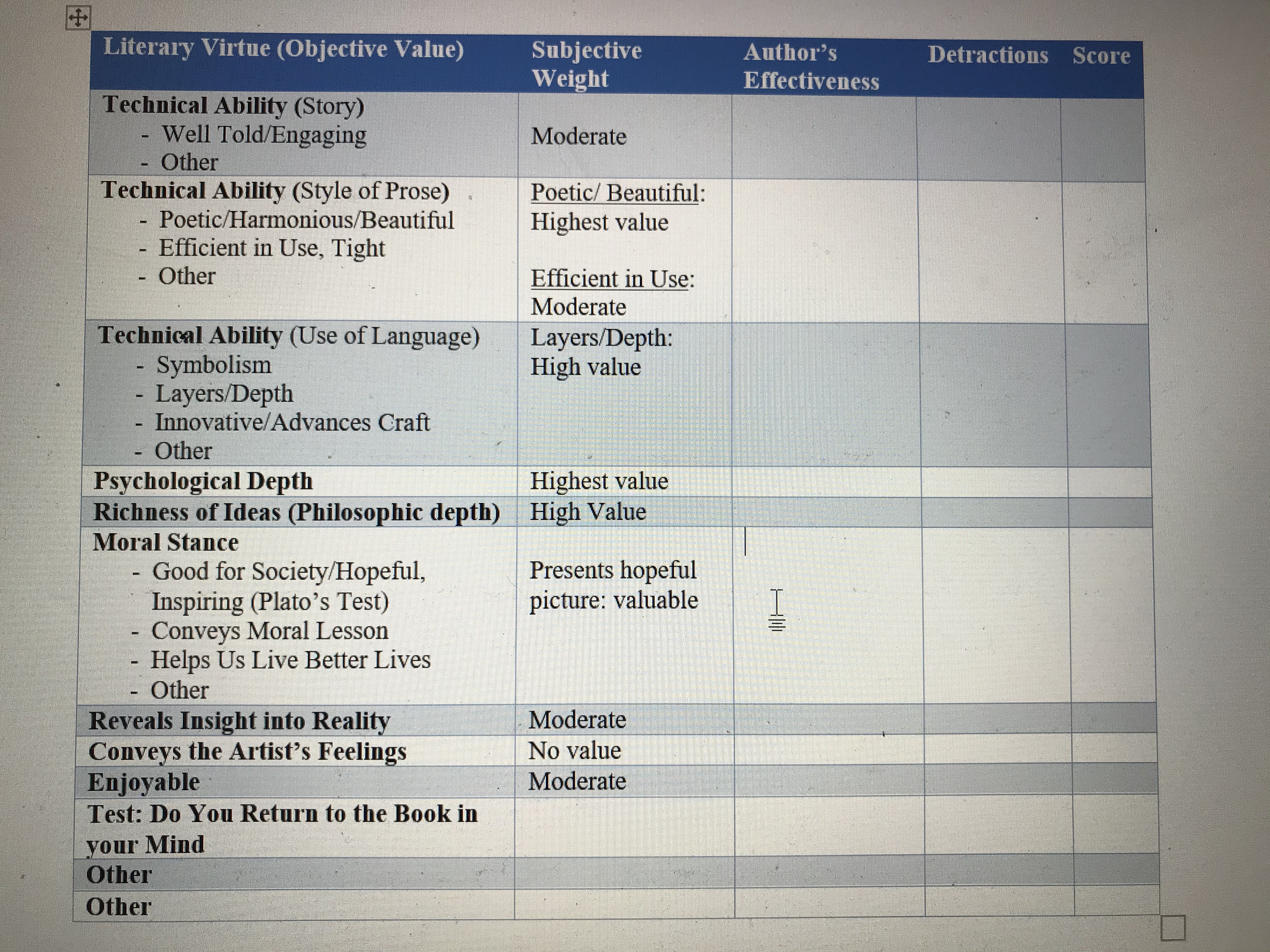

Score Card with Subjective Weights

These items are all listed in “score” card below along with a couple “open” fields for unique qualities of a work. The “subjective weight” listed in each field is my own. I greatly value the poetic and psychological depth. A good story is nice, but does not carry as much weight.

Finally, I list a place for “Detractors.” Sometimes there will be something about a book, that takes away from its quality. Depending upon the item, this could be either an objective assessment, or subjective preference. For example, while at times Don Quixote is funny, the frequent violence the main character inflicts on innocent people took a great deal away from the book for me.

©2020, John Albert Doyle, Jr.

Pingback: The Why of Art – Sean Doyle